Immigration to Australian continent is estimated to have begun around 50,000 years ago[1] when the ancestors of Australian Aborigines arrived on the continent via the islands of the Malay Archipelago and New Guinea.

Europeans first landed in the 1600s and 1700s, but colonisation only started in 1788.

The overall level of immigration has grown substantially during the last decade and a half. Net overseas migration increased from 30,042 in 1992-93[2] to 177,600 in 2006-07.[3] This is the highest level on record. The largest components of immigration are the skilled migration and family re-union programs. In recent years the mandatory detention of unauthorised arrivals by boat has generated great levels of controversy.

During 2004-05, a total of 123,424 people immigrated to Australia. Of them, 17,736 were from Africa, 54,804 from Asia, 21,131 from Oceania, 18,220 from United Kingdom, 1,506 from South America, and 2,369 from Eastern Europe.[4]

131,000 people migrated to Australia in 2005-06[5] and migration target for 2006-07 was 143,000.[6] The planning level for the 2007–08 Migration Programme has been set in the range of 142 800 to 152 800 places, plus 13 000 in the Humanitarian Programme.[7] Australia opens its doors to about 300,000 new migrants in 2008-09 - its highest level since the Immigration Department was created after World War II.[8][9]

History

Human migration to the Australian continent was first achieved during the closing stages of the Pleistocene epoch, when sea levels were typically much lower than they are today. It is theorised that these ancestral peoples arrived via the nearest islands of the Malay Archipelago, crossing over the intervening straits (which were then narrower) to reach the single landmass which then existed. Known as Sahul, this landmass connected Australia with New Guinea via a land bridge which emerged when prevailing glacial conditions lowered sea levels by some 100-150 metres. Australia's coastline also extended much further out into the Timor Sea than at present, affording another possible route by which these first peoples reached the continent. Estimates of the timing of these migrations vary considerably: the most widely-accepted conservative evidential view places this somewhere between 40,000 to 45,000 years ago, with earlier cited (but not universally accepted) dates of up to 60,000 years or more also proposed; the debate continues within the academic community.

On 26 January 1788, a date now celebrated as Australia Day - but regarded as "Survival Day" or "Invasion Day" by some Aboriginal people and supporters,[10] the British First Fleet of Penal transportation ships landed at Sydney Cove for the purposes of establishing a penal colony. The new colony was formally proclaimed as the Colony of New South Wales on 7 February.

The colony was originally mostly a penal colony with a minority of free settlers. From the very first days of settlement, it was necessary to obtain leave to migrate to Australia. Since the cost of travelling from Europe was much higher than going from there to the United States, the colonies found it difficult attracting migrants. In the 1840s this was overcome by using the ideas of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, who proposed that land prices be kept high, and the money used to subsidise immigrants. This continued until self-government was achieved, when the electors refused to sanction tax money being used to provide competitors for available jobs.

The Gold rush era, beginning in 1851, led to an enormous expansion in population, including large numbers of British and Irish settlers, followed by smaller numbers of Germans and other Europeans, and Chinese. This latter group were subject to increasing restrictions and discrimination, making it impossible for many to remain in the country. With the Federation of the Australian colonies into a single nation, one of the first acts of the new Commonwealth Government was the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, otherwise known as the White Australia policy, which was a strengthening and unification of disparate colonial policies designed to restrict non-White settlement. Because of opposition from the British government, an explicit racial policy was avoided in the legislation, with the control mechanism being a dictation test in a European language selected by the immigration officer. This, of course, was selected to be one the immigrant didn't know, and the last time an immigrant passed a test was in 1909. Perhaps the most celebrated case was Egon Erwin Kisch, a left-wing Czechoslovakian journalist, who could speak five languages, who was failed in a test in Scottish Gaelic, and deported as illiterate.

The federal government also found that if it wanted immigrants it had to subsidise migration. It was very easy to control the number of immigrants needed during different stages of the economic cycle by varying the subsidy.

With the onset of the great depression, the Governor-General proclaimed the cessation of immigration until further notice, and the next group to arrive were 5000 Jewish refuge families from Germany in 1938. Approved groups such as these were assured of entry by being issued with a Certificate of Exemption from the Dictation Test.

After World War II, Australia launched a massive immigration programme, believing that having narrowly avoided a Japanese invasion, Australia must "populate or perish." Hundreds of thousands of displaced Europeans migrated to Australia and over 1,000,000 British Subjects immigrated under the Assisted Migration Scheme, colloquially becoming known as Ten Pound Poms. The qualifications were very simple; if you were of European ancestry, reasonably healthy, and without a criminal record, you would be accepted.

Around 1970 there was a fundamental change in immigration policy, since for the first time since 1788 there were more migrants wanting to come (even without a subsidy) than the government wanted to accept. All subsidies were abolished, and immigration became progressively more difficult.

During the 2001 election campaign, asylum-seekers and border protection became a hot issue, as a result of incidents such as the 11 September 2001 attacks, the Tampa affair, Children overboard affair, and the sinking of the SIEV-X. This incident marked the beginning of the controversial Pacific Solution. The Howard government's success in the election was largely due to the strong public support for its restrictive policy on asylum-seekers. However, the overall level of immigration increased substantially over the life of the Howard Government.

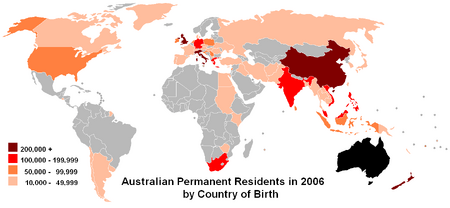

Country of birth of Australian residents

Countries of birth of Australian estimated resident population, 2006.

Source:Australian Bureau of Statistics[11]

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics[12] in mid-2006 4,956,863 of the Australian resident population were born outside Australia, representing 24% of the total Australian resident population.

| Country of Birth | Estimated Resident Population[13]

|

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 1,153,264 |

| New Zealand | 476,719 |

| China | 279,447 |

| Italy | 220,469 |

| Vietnam | 180,352 |

| India | 153,579 |

| Philippines | 135,619 |

| Greece | 125,849 |

| South Africa | 118,816 |

| Germany | 114,921 |

| Malaysia | 103,947 |

| Netherlands | 86,950 |

| Lebanon | 86,599 |

| Sri Lanka | 70,908 |

| Serbia and Montenegro | 68,879 |

| Indonesia | 67,952 |

| United States | 64,832 |

| Poland | 59,221 |

| Fiji | 58,815 |

| Ireland | 57,338 |

| Croatia | 56,540 |

Settlement patterns

There are some differences in settlement patterns, as demonstrated in the statistics compiled at the 2006 Census.[14]

New South Wales has the largest population, and the largest foreign born population, in Australia (1,544,023). Certain nationalities are highly concentrated in this state: 74.5% of Lebanese-born, 63.1% of Iraqi-born, 63.0% of South Korean-born, 59.4% of Fijian-born and 59.4% of Chinese-born Australian residents live in New South Wales.

Victoria, the second most populous state, also has the second largest number of overseas-born persons (1,161,984). 50.6% of Sri Lankan-born, 50.1% of Turkish-born, 49.4% of Greek-born and 41.6% of Italian-born Australian residents were enumerated in this state.

Western Australia, with 528,827 overseas-born residents, has the highest proportion of its population being foreign-born. The state attracts 29.6% of all Singapore-born Australian residents, and is narrowly behind New South Wales in having the largest population of British-born.

Queensland had 695,525 overseas-born residents, and attracted the greatest proportion of persons born in Papua New Guinea (52.4%) and New Zealand (38.2%).

Environmental, economic and social impacts

There are a wide range of views in the Australian community on the composition and level of immigration, and on the possible effects of varying the level of immigration and population growth, some of which are based on empirical data, others more speculative in nature. In 2002, a CSIRO population study entitled "Future Dilemmas", commissioned by DIMA, outlined six potential dilemmas associated with immigration-driven population growth. These dilemmas included the absolute numbers of aged continuing to rise despite high immigration off-setting ageing and declining birth-rates in a proportional sense, a worsening of Australia's trade balance due to more imports and higher consumption of domestic production, increased green house gas emissions, overuse of agricultural soils, marine fisheries and domestic supplies of oil and gas, and a decline in urban air quality, river quality and biodiversity.[15]

Environment

Some members of the Australian environmental movement, notably the organisation Sustainable Population Australia, believe that as the driest inhabited continent, Australia cannot continue to sustain its current rate of population growth without becoming overpopulated. SPA also argues that climate change will lead to a deterioration of natural ecosystems through increased temperatures, extreme weather events and less rainfall in the southern part of the continent, thus reducing its capacity to sustain a large population even further.[16] The UK-based Optimum Population Trust supports the view that Australia is overpopulated, and believes that to maintain the current standard of living in Australia, the optimum population is 10 million (rather than the present 20.86 million), or 21 million with a reduced standard of living.[17]

It is argued that immigration exacerbates climate change, because immigrants generally come from countries with low greenhouse gas emissions per capita to countries with high per capita emissions (like Australia). A number of climate-change observers see population control as essential to arresting global warming.[18] Analysis by The Australia Institute shows that Australia’s population growth has been one of the main factors driving growth in domestic greenhouse gas emissions. It further finds that the average emissions per capita in the countries that immigrants come from is only 42% of average emissions in Australia, meaning that as immigrants alter their lifestyle to that of Australians, they increase global greenhouse gas emissions.[19] It is calculated that each additional 70,000 immigrants will lead to additional emissions of 20 million tones of greenhouse gases by the end of the Kyoto target period (2012) and 30 million tonnes by 2020.[20] In contradiction to this, a study in science journal Nature claims that immigration does not result in global warming because although immigration increases population in one country, on a global level immigration does not affect population.[21]

Housing

Some claim that Australia's recent level of immigration has (along with natural population growth and a range of other economic factors) contributed to a widespread shortage of affordable housing, particularly in the major cities.[22] A number of economists, such as Macquarie Bank analyst Rory Robertson, assert that high immigration and the propensity of new arrivals to cluster in the capital cities is exacerbating the nation's housing affordability problem.[23] According to Robertson, Federal Government policies that fuel demand for housing, such as the currently high levels of immigration, as well as capital gains tax discounts and subsidies to boost fertility, have had a greater impact on housing affordability than land release on urban fringes.[24] However, the Productivity Commission does not accept "population pressures" as a major driver of strong increases in house prices, stating that "increased demand for better quality and better located dwellings, rather than for more dwellings, has been the primary driver".[25]

Employment

According to one researcher, there are thousands of low-cost IT workers entering Australia who are undermining the job prospects of new computer science graduates and reducing salaries in the IT industry.[26] However, other research sponsored by DIAC has found that Australia’s structured labour market along with the larger number of immigrants with higher education levels has tended to raise employment levels for Australians who are relatively unskilled.[27]

Australian trade unions have sometimes exposed attempts by employers to introduce foreign workers into the country in order to avoid paying local workers higher wages.[28]

Economy

The former Federal Treasurer, Peter Costello considers that Australia is underpopulated due to low birth rate, and claims that negative population growth will have adverse long-term effects on the economy as the population ages and the labour market becomes less competitive.[29] To avoid this outcome the government has increased immigration to fill gaps in labour markets and introduced a subsidy to encourage families to have more children. However, opponents of population growth such as Sustainable Population Australia do not accept that population growth will decline and reverse, based on current immigration and fertility projections.[30]

There is uncertainty over whether immigration can slow the ageing of Australia's population. In a research paper entitled Population Futures for Australia: the Policy Alternatives, Peter McDonald claims that "it is demographic nonsense to believe that immigration can help to keep our population young."[31] However, according to Creedy and Alvarado (p. 99),[32] by 2031 there will be a 1.1 per cent fall in the proportion of the population aged over 65 if net migration rate is 80,000 per year. If net migration rate is 170,000 per year, the proportion of the population aged over 65 would reduce by 3.1 per cent. As of 2007 during the leadership of John Howard, the net migration rate was 160,000 per year.[33]

The former Immigration Minister from the Howard Government Kevin Andrews supported the use of immigration to slow population ageing in Australia.[34] He said, "The level of net overseas migration is important as net inflows of migrants to Australia reduce the rate of population ageing because migrants are younger on average than the resident population. Just under 70% of the migrant intake are in the 15 – 44 age cohort, compared to 43% of the Australian population as a whole. Just 10% of the migrant intake are 45 or over, compared with 38% of the Australian population."

Ross Gittins, an economics columnist at Fairfax Media, backs up the Immigration Minister, claiming that the Liberal Party's focus on skilled migration has reduced the average age of migrants. "More than half are aged 15 to 34, compared with 28 per cent of our population. Only 2 per cent of permanent immigrants are 65 or older, compared with 13 per cent of our population."[35] Because of these statistics, Gittens claims that immigration is slowing the ageing of the Australian population. He also claims that the emphasis on skilled migration also means that the "net benefit to the economy is a lot more clear-cut." Even though Gittens suggests that skilled workers add more to the economy, there are those who acknowledge the importance of unskilled migrants. Treasurer Eric Ripper claims that in Australia "several major capital works projects had to be put on hold because there were not enough skilled and unskilled workers."[36]

Using regression analysis, Addison and Worswick found that “there is no evidence that immigration has negatively impacted on the wages of young or low-skilled natives.” Furthermore, Addison's study found that immigration did not increase unemployment among native workers. Rather, immigration decreased unemployment.[37]

In July 2005 the Productivity Commission launched a commissioned study entitled Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth,[38] and released an initial position paper on 17 January 2006[39] which states that the increase of income per capita provided by higher migration (50% more than the base model) by the 2024-2025 financial year would be $335 (0.6%), an amount described as "very small." The paper also found that Australians would on average work 1.3% longer hours, about twice the proportional increase in income.[40]

In a study in the Australian Economic Review, Junankar finds that immigration during the 1980s Hawke Government lowered the unemployment rate[41]

Gittens claims there is considerable opposition to immigration in Australia by "battlers" because of the belief that immigrants will steal jobs. Gittens claims though that "it's true that immigrants add to the supply of labour. But it's equally true that, by consuming and bringing families who consume, they also add to the demand for labour - usually by more."[35]

Infrastructure

Individuals and interest groups such as Sustainable Population Australia filed submissions in response to the Productivity Commission's position paper, arguing amongst other things that immigration causes a decline in wealth per capita and leads to environmental degradation and overburdened infrastructure, the latter creating a costly demand for new infrastructure.[42][43] However, the Productivity Commission's final research report found that it was not possible to reliably assess the impact of environmental limitations upon productivity and economic growth, nor to reliably attribute the contribution of immigration to any such impact.[44]

Australia is a relatively high-immigration country like Canada (the country with the highest per capita immigration rate in the world, see Immigration to Canada) and the United States, and while other economically developed countries like Japan have historically had negligible immigration,[45] the issue of population decline is forcing a rethink of such policies.

Nobel laureate economist Gary Becker from the University of Chicago, in a piece published in the Wall Street Journal, wrote, “The only solution for countries that continue to be concerned about a future with declining and aging populations is to open their gates to immigration. Yet in most countries large-scale immigration creates political, economic and social problems. Immigration is an especially unwelcome alternative for Japan, given the history of Japanese reluctance to have many foreigners settling in their country. As a result, Japan, Russia and many other countries face a worrisome demographic and economic future.”[45]

Immigration and Australian politics

Both major Australian political parties favour a relatively high level of immigration. When John Howard became Prime Minister, net migration was rising, and the upward trend in the number of immigrants increased over the decade from when he took office in 1996. According to Banham, Australian political leaders who support higher immigration include Amanda Vanstone, John Howard, Peter Costello, Kim Beazley, and Steve Bracks, with vocal opposition to immigration coming from former New South Wales premier Bob Carr who cites environmental reasons for his opposition.[46] Peter Costello believes that high population growth in Australia is important for economic growth.[47]

Commentators such as Ross Gittens, a columnist at Fairfax Media accused former Prime Minister John Howard of deception, by appearing "tough" on illegal immigration to win support from the working class while simultaneously winning support from employers with high legal immigration.[48]

In 2006, the Labor Party under Kim Beazley took a stance against the importation of increasingly large numbers of temporary migrant workers ("foreign workers") by employers, arguing that this is simply a way for employers to drive down wages.[49] At the same time, it is estimated that a million Australians are employed outside Australia.[50]

According to a 2007 Liberal Party document titled Immigration - Its Role in Our Future, the Coalition's immigration policy is "free from discrimination based on race, religion, gender, nationality or country of origin."[51][52] After blocking African migrants, the document was taken down from the Liberal Party's main website.

An anti-immigration party, the One Nation Party, was formed by Pauline Hanson in the late 1990s. The party enjoyed significant electoral success for a while, most notably in its home state of Queensland, but is now electorally marginalized. One Nation argued for a zero net immigration policy, asserting that "environmentally Australia is near her carrying capacity, economically immigration is unsustainable and socially, if continued as is, will lead to an ethnically divided Australia."[53]

The Liberal Party's policy of mandatory detention, especially regarding the impact upon children, has come under criticism from a range of religious, community and political groups including the National Council of Churches, Amnesty International, Australian Democrats, Australian Greens and Rural Australians for Refugees.

Announced by the Kevin Rudd federal Labor government in July 2008, Mandatory detention in Australia will cease, unless the person claiming asylum is deemed to pose a risk to the wider community, such as those who have repeatedly breached their visa conditions or those who have security or health risks.[54]

Migration agents

It is possible to employ migration agents or lawyers to assist with a visa application to Australia. Such persons who provide immigration assistance are regulated by a governing Authority called the Migration Agents Registration Authority. Although there is a significant difference in education and training between migration agents and lawyers, migration agents must complete a Graduate Certificate in Migration Law and Practice. However since 1998 over 18% of the MARA’s sanction decisions have been against lawyer agents with a legal practising certificate. To identify how many years an agent has been registered from, the first two numbers of their seven digit registration number will show the year. Only agents registered pre 28 March 1998 can have a five digit number.[55]

Migration and settlement services

There are a variety of community-based services that cater to the needs of newly-arrived migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, some of which receive funding from the Commonwealth Government, such as Migrant Resource Centres. Asylum seekers, however, are denied access to such services and there are only a very small number of specific asylum seeker services catering to their needs.

See also

- Demography of Australia

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship

- ChilOut (Children Out of Detention)

- Template:MV

- Post war immigration to Australia

References

- ↑ Smith, Debra (2007-05-09). Out of Africa - Aboriginal origins uncovered. The Sydney Morning Herald. “Aboriginal Australians are descended from the same small group of people who left Africa about 70,000 years ago and colonised the rest of the world, a large genetic study shows. After arriving in Australia and New Guinea about 50,000 years ago, the settlers evolved in relative isolation, developing unique genetic characteristics and technology.”

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics, International migration

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics, 3101.0 Australian Demographic Statistics

- ↑ Inflow of foreign-born population by country of birth, by year

- ↑ Settler numbers on the rise

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Government - Department of Immigration and Citizenship: Key Facts in Immigration

- ↑ Australian Immigration Fact Sheet 20. Migration Program Planning Levels

- ↑ Immigration intake to rise to 300,000, 11/06/2008

- ↑ 300,000 skilled workers needed - Evans, NEWS.com.au

- ↑ Australia Day and Reconciliation - accessed 12/09/07

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics, accessed 9 December 2007

- ↑ 3412.0 Migration, Australia (2005-06)

- ↑ [1]. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2006. Last accessed 18 November 2007.

- ↑ 2006 Census Data : View by Location Or Topic

- ↑ Foran, B., and F. Poldy, (2002), Future Dilemmas: Options to 2050 for Australia's population, Technology, Resources and Environment, CSIRO Resource Futures, Canberra.

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20070828215443/http://www.population.org.au/media/mediarels/mr20061023.pdf

- ↑ Optimum Population Trust

- ↑ Rich nations blamed for global warming, but not for all the right reasons

- ↑ Population Growth and Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- ↑ High Population Policy Will Double Greenhouse Gas Growth

- ↑ Access : : Nature

- ↑ People & Place Volume 11, Issue 3 (2003), Migration and the Housing Affordability Crisis, Birrell, B. and Healy, E

- ↑ Klan, A. (17 March 2007) Locked out

- ↑ Wade, M. (9 September 2006) PM told he's wrong on house prices

- ↑ Productivity Commission, First Home Ownership Inquiry Report, p.63 (final par.) & p.68

- ↑ Australian Financial Review 7/7/04, “Immigrants taking local IT jobs: report”

- ↑ DIMA research publications (Garnaut), Migration to Australia and Comparisons with the United States: Who Benefits?, p.21

- ↑ LaborNET Foreign Labour Used to Lower Wages

- ↑ Costello hatches census-time challenge: procreate and cherish - National

- ↑ Goldie, J. (23 February 2006) "Time to stop all this growth" (retrieved 30 October 2006)

- ↑ McDonald, P., Kippen, R. (1999) Population Futures for Australia: the Policy Alternatives

- ↑ Population Ageing, Migration and Social Expenditure

- ↑ Farewell, John. We will never forget you - Federal Election 2007 News

- ↑ http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/media/speeches/2007/ka02-17052007.htm

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Back-scratching at a national level - Opinion - smh.com.au

- ↑ Still work to do on skills shortage | The Australian

- ↑ Addison, T. and Worswick, C. (2002). The impact of immigration on the earnings of natives: Evidence from Australian micro data. Economic Record, Vol. 78, pp. 68-78.

- ↑ http://www.pc.gov.au/study/migrationandpopulation/index.html

- ↑ Productivity Commission, Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth (Position Paper), p.73

- ↑ Productivity Commission, Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth Key Points

- ↑ Junankar, P., Pope, D. and Withers, G. (1998). Immigration and the Australian macroeconomy: Perspective and prospective. Australian Economic Review, Vol. 31, pp. 435-444.

- ↑ Claus, E (2005) Submission to the Productivity Commission on Population and Migration (submission 12 to the Productivity Commission's position paper on Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth).

- ↑ Nilsson (2005) Negative Economic Impacts of Immigration and Population Growth (submission 9 to the Productivity Commission's position paper on Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth).

- ↑ Productivity Commission, Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth (Research Report), p.119

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 The Wall Street Journal Online - Extra

- ↑ Banham, C. (2004, 2 April). Door opens to 6000 more immigrants. Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 October from http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/04/01/1080544631282.html

- ↑ Population or immigration: Costello issues warning - National - theage.com.au

- ↑ Gittens, R. (2003, 20 August). Honest John's migrant twostep. The Age. Retrieved 2 October from http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2003/08/19/1061261148920.html

- ↑ “Workers of the World”, Background Briefing, Radio National Sunday 18 June 2006

- ↑ http://www.abc.net.au/rn/backgroundbriefing/stories/2006/1662023.htm#transcript “Workers of the World”], Background Briefing, Radio National Sunday 18 June 2006

- ↑ 403 Forbidden

- ↑ http://www.ozpolitics.info/election2004/2001LNP/immigration-policy.pdf

- ↑ One Nation's Immigration, Population and Social Cohesion Policy 1998

- ↑ Sweeping changes to mandatory detention announced: ABC News 29/7/2008

- ↑ 2007–08 Review of Statutory Self-Regulation of the Migration Advice Profession Discussion Paper September 2007 http://web.archive.org/web/20090318080336/http://www.themara.com.au/ArticleDocuments/114/self-reg-mig-advice-prof.pdf

- Commonwealth of Australia. Migration Act 1958

- Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs. Fact Sheet 82, Immigration Detention, 2004

External links

- Economic Benefits of Migration, DIMIA 2002.

- Worswick, C. The Economics of the Immigration Debate, Department of Economics, University of Melbourne.

- Costello hope for skilled migrant intake

- NSW training Chinese workers

- Origins: Immigrant Communities in Victoria - Immigration Museum, Victoria, Australia

- NSW Migration Heritage Centre, Australia

- The Migration Agents Registration Authority (The MARA)

- Foreigners with TB, leprosy may be banned

- Australian State of Queensland skilled and business migration information site

- Victoria government immigration site

Template:Oceania topic

|

This page uses content from Immigration to Australia at the English Wikipedia, which is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. |